If Australian companies can ditch the megaphone and get the relationship right with Asian export markets, they can be richly rewarded, a new report says.

Companies bemoaning the bilateral tensions between Australia and China must understand that seemingly maverick decisions by Chinese authorities are part and parcel of conducting business with the world's second-biggest economy. As a result they need to double down on their efforts to improve relations with Chinese government and regulatory officials.

Standing on a soapbox and shouting about China's contribution to Australia's national prosperity is not the answer.

That is the advice from China experts who spoke to AFR BOSS ahead of the launch next Tuesday of a new report, Winning in Asia, spearheaded by advisory firm Asialink Business.

Getting the relationship with China right – as well as with other export markets – can be richly rewarded.

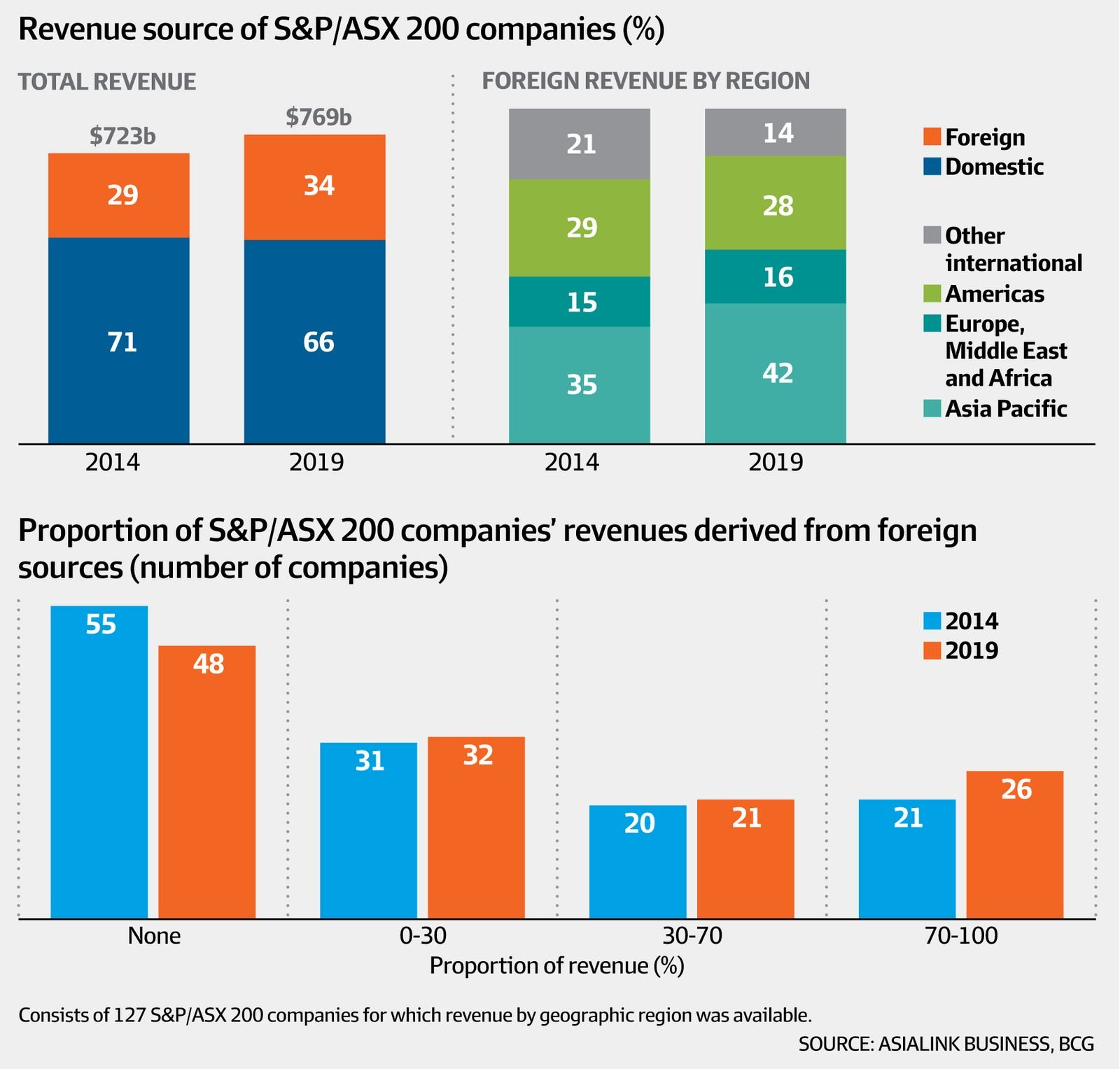

Among 83 companies with a market value of more than $2 billion, those that were internationally diversified recorded substantially higher shareholder returns than their domestically focused counterparts over the past five years, the report found.

Companies capitalised at between $2 billion and $5 billion, and deriving more than 10 per cent of their revenue offshore, recorded an average total shareholder return of 20 per cent between 2014 and 2019, against an 11 per cent total return for companies reliant on the Australian market for the vast bulk of their sales.

For companies valued at more than $5 billion, those that were internationally diversified returned a total of 15 per cent annually between 2014 and 2019, substantially higher than the 11 per cent total shareholder return posted by domestically oriented companies.

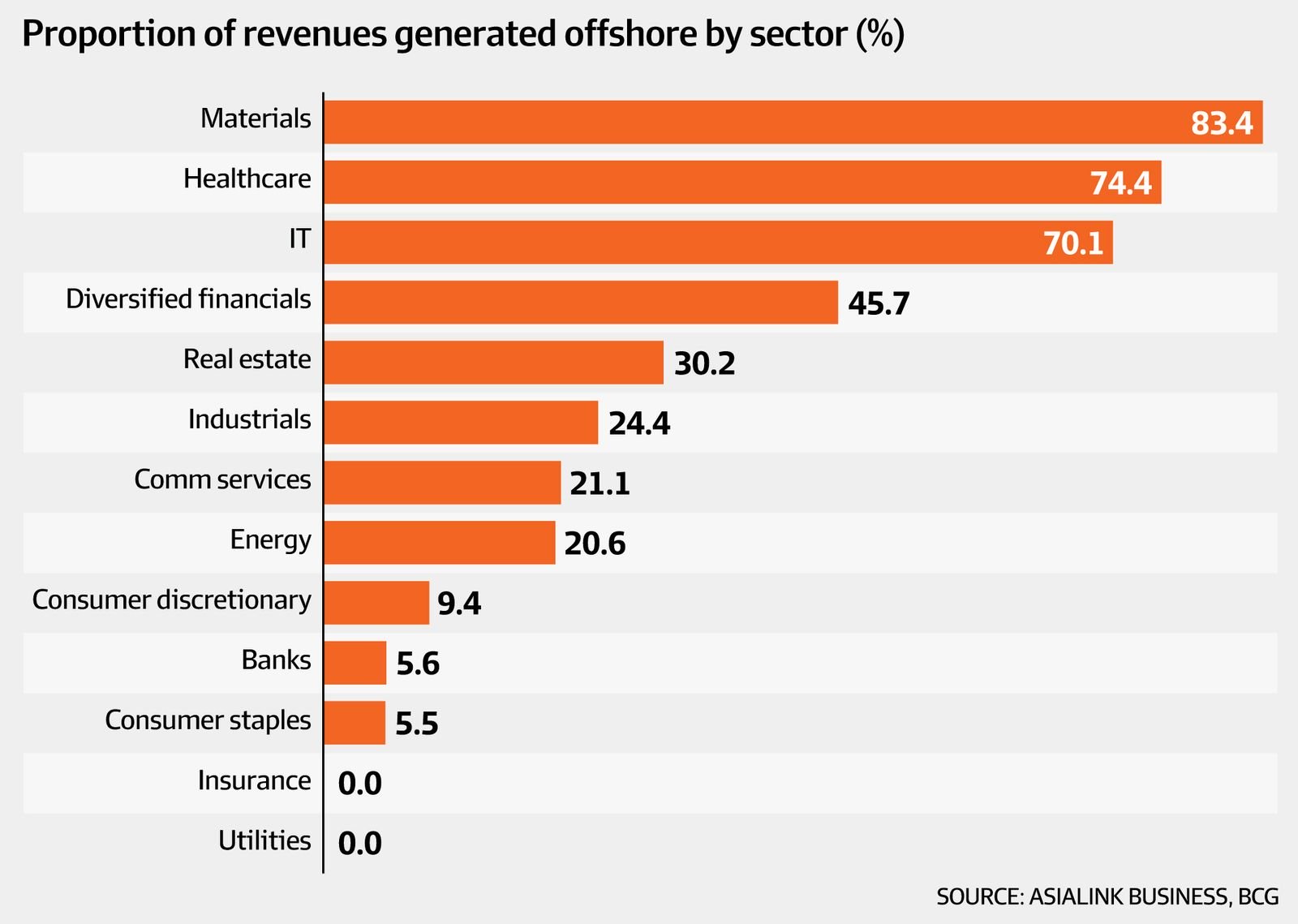

Besides miners, the sectors among ASX 200 companies that derive the largest share of revenues from offshore are healthcare, information technology, diversified financials and real estate, according to the report, which was co-published by Commonwealth Bank of Australia, the Australian Institute of Company Directors, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand and The Sid and Fiona Myer Family Foundation.

The report concludes there is no uniform answer to successful offshore expansion, and Asialink Business CEO Mukund Narayanamurti points to the significant achievements recorded by Australian companies exporting offshore, including to Asia.

"We do understand Asia. Our leaders are quite savvy," Narayanamurti says, noting that among ASX 200 companies, the share of foreign revenues derived from the Asia-Pacific grew to 42 per cent from 35 per cent between 2014 and 2019.

Despite China's share of Australian exports reaching an all-time high in June, rising to 48.8 per cent, Narayanamurti points to mistakes Australian companies are still making in China, which has a 400 million-strong middle class. One failing is Australian companies' lack of government and regulatory relations teams and corporate affairs teams, which might be able to either influence policy or detect impending policy and regulatory changes.

"Australian companies are lighter than their US, European and Japanese counterparts in external affairs. So their ability to engage with government and regulators is compromised," Narayanamurti says. If changes were afoot, companies would be able to "inform the regulator about the impact on their industry more broadly", he adds.

Narayanamurti argues Australian companies also need to think about the products and services they export to China and how these align with Beijing's national agenda.

"That level of interdependency is really important. It needs to be deeply entrenched," he says. Iron ore is a case in point, as are medical devices and aged care.

Qiao Ma, portfolio manager of the Asian Equities Fund at Cooper Investors and one of the co-authors of the report, agrees that having external affairs staff on the ground is critical.

"[Decisions] don't come out of the blue," Ma says, adding that companies considered to have "thoughtful thinkers" are more likely to be consulted.

Ma points out that local companies are also exposed to the regulatory winds.

"Just because you are a domestic Chinese company doesn't mean your products are exempt from certain regulatory scrutiny," she says. "Every industry faces an ebb and flow of regulatory tightness and loosening. It really goes in a cycle."

Even Chinese tech giant Tencent, whose cash engine is gaming, has faced regulatory hurdles. In 2018 regulators stopped approving commercial licences for online games for about eight months. Ma says Tencent management realised that if the environment was tough for Tencent, it was tough for everyone. The company put effort into its relationship with the regulators and diversified its business model.

"In some ways it is a relative game. If you are more organised, if you have a proper [external affairs] business unit set up, if you treat regulators as a partner whose relationship you need to actively manage, you tend to come out better than your competitors," Ma says.

She notes Tencent and a key competitor that was also caught up in the ban never complained and never bad-mouthed the regulators.

"They said: 'We have to adapt. We have to change. And if we do it better than everybody else, we're going to come out OK.' It was a very tenacious attitude."

Respect for multinational experience

Foreign companies need to understand the strength of the local competition and the tendency for local Chinese companies to be run by well-educated executives who have advanced degrees from offshore universities and experience working for multinationals.

They should also treat their Chinese subsidiaries like a start-up, so they are nimble, agile organisations that can quickly adapt to changing customer, consumer and regulatory demands.

Given the need to be close to the ground and invest in local talent, distribution systems and IT, an "asset light" approach in the form of a small China-representative office won't cut it.

The Winning in Asia report notes that marketing and distribution are traditional strengths for many domestic Chinese companies. China Mengniu, which last year acquired organic infant formula company Bellamy's, operates a national distribution network that takes in 1.5 million points of sale, which it is digitising. The company is partnering with Alibaba using its inventory management platform to boost market penetration.

What is not needed, says Narayanamurti, is megaphone diplomacy.

"Narrowcast is the best way to engage with a large, complex and strategic partner. Just because this isn't visible doesn't mean it isn't happening. Our exports with China are up this year despite all the reported negative sentiment. Business is getting on with business," he says, adding that any resumption of annual meetings between Australian and Chinese business leaders would also be unlikely to have a big impact.

"Opportunities for bilateral engagement can only ever be helpful. However, once-off or annual gatherings can be more ceremonial than deeply meaningful. Annual meetings should be complemented by an ongoing program of engagement with clear, mutually beneficial strategic objectives that the business leaders on both sides are invited to play a key role in facilitating."

India is another major focus of the report, which was overseen by a taskforce of business leaders including Christine Holgate, CEO of Australia Post, Peter Varghese, chancellor of the University of Queensland, and Wesfarmers director Diane Smith-Gander.

Perhaps the first thing to remember is that India is not the next China. Report co-author Mary Manning, portfolio manager at asset manager Ellerston, says India is a large, populous country with a high rate of growth, but that is where the similarities with China end. It is an economy fuelled by domestic demand, although it cannot support high-end goods such as high-quality beef, fish and formula milk because of its low GDP per capita. India has its own supply of iron ore and is a democracy.

India is the world's fifth-largest economy with a GDP of more than $US3 trillion ($4.2 trillion) and a population of 1.4 billion. By 2030 it is expected to be the world's third-largest economy after China and the US. Despite its size, however, the country remains largely ignored by Australian companies in foreign investment terms. In 2018 only about 0.6 per cent of Australian outbound investment was directed to India.

One of the biggest reasons companies fail in India is because they fail to localise, argues Manning. "You can't just go to India and expect to have the strategy you use at home or for other Asian countries," she says. "It's not just an export market. You need to have people on the ground."

Manning notes that the short-term outlook for India is weak, given the spread of COVID-19, but says it is a good time for companies to be analysing the market and "putting feelers out".

One Australian company to build a successful Indian operation, the report notes, is Macquarie Group, which established a securities broking business in 2005 to complement the investment bank's wider Asian strategy. The bank has since established real estate and infrastructure funds, making it the largest foreign investor in Indian roads.

This article was originally posted in ARF's BOSS here.

Cooper Investors is one of our Core Fund Managers.

Licensed by Copyright Agency. You must not copy this work without permission.